Don't want to clean chitlins? These Detroit stores will do it for you

'Chitterling cleaners' help keep a culinary tradition alive -- and keep customers coming

In the back of Gourmet Food Center, it’s quiet. Soothingly quiet. On the outside of the store, located at the corner of Plymouth and Greenfield roads, people are in and out of the gas station on one side and an outlet of Hot Wheel City, the flashy rims store better known for its more luminous display on West Eight Mile, on the other side. If not for GPS, a first-time visitor can easily pass it before arriving. Once you’re inside, outside noise dissipates.

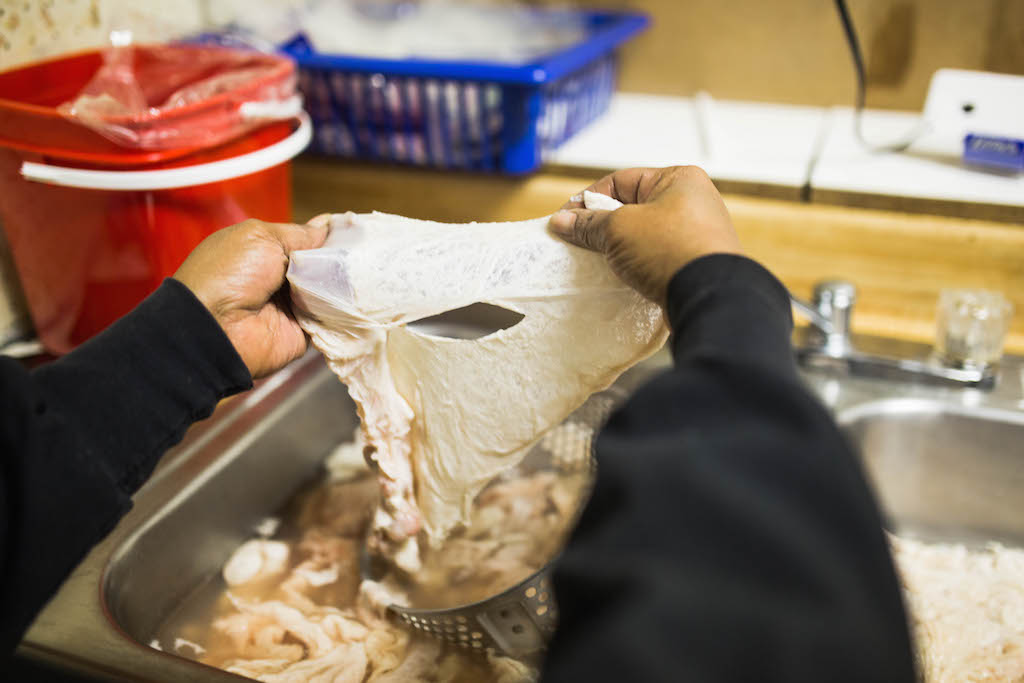

When you walk inside, you first smell bleach. As the chlorine settles in your nostrils, then then smell is more akin to a butcher shop. In the back, behind the customer service area, four workers in white aprons and coveralls silently peel, shear and slice away at pig intestines and stomach linings.

They’re chitterling cleaners.

“I’ve had so many people tell me we clean them too good, But that’s because in the olden days, they didn’t clean them like we cleaned them,” Gourmet Food Center CEO Bruce Tucke says.

I can’t resist the urge of calling this a chitlin circuit, but what Tucker has here is exactly that. Tucker and his wife, Cynthia, own three Gourmet Food Center locations: the one here on Greenfield and Plymouth, its flagship location on West Seven Mile and Greenfield, and a third location on East Kirby in Poletown. The distinction between the eastside location and the two on the westside is that uncleaned chitterlings and hog maws — the ones that home cooks insist they clean themselves — can be had on the eastside, so it smells more. To keep the smell of hundreds of pounds of pig innards at bay, bleaching surfaces on a regular basis is a must.

For the uninitiated, chitterlings are the culinary term for pig intestines and hog maws are pig stomach linings. Careful sanitizing is obviously required of all meats, but special attention to is paid to the cleaning of these innards, especially the intestines. It’s no wonder why on Gourmet Food Center’s website, with the apt URL ChitterlingCleaners.com) its mission statement reads, “We clean the sh*t out of chitlins!”

No one wants to eat pig feces, which is why the skill of chitterling cleaning is a honed practice in the Gourmet Food Center locations. The Tuckers have been in the business for 30 years this year; many have been with the company for at least five years, some nearly 20.

“We were cleaning chitlins every day, and we were doing better than say, your grandmother who does it once or twice a year,” Bruce Tucker says. “We got better and our reputation grew. A lot of it is word of mouth; everybody’s not intimidated by chitlins.”

Maybe not everybody, but several people are. I have no data, but I’m willing to bet there’s been a generational shift in attitudes toward chitlins, perhaps divided squarely on millenial lines. I’m biased, as I have fond memories from each year of my childhood of my grandmother — Conant Gardens upbringing with North Carolina roots — going to the store to get the familiar red bucket reading “Pork Chitterlings” on top. I remember the hours of cleaning them, and the subsequent hours of cooking them in her Presto pressure cooker. She passed on her cleaning skills to my mother, and my mother lucked up and married a man who loved — and still loves — all parts of a pig, feet included, and can clean them himself. I guess we’re just some chitlin-eating MFs around here.

“I’ve had so many people tell me we clean them too good, But that’s because in the olden days, they didn’t clean them like we cleaned them."

Not everyone shares that sentiment. My father is the one who brings the chitlins to our family gatherings, much to the chagrin of my siblings and cousins around my age who hate the taste and smell. A casual survey of my Facebook friends recommend the best way of cooking chitlins is to “throw them in the trash.” And when I announced to our Media Services department that I was looking for volunteers to help with this chitlin piece, the vast majority of my co-workers winced and immediately declined.

The reasons? Well, the smell. The texture. The oddity of it all — what are chitterlings anyway, and why do we have to go through all this to clean the poop out? It is frequently derided in pop culture (tell me you didn’t think of Hustle Man’s chitlin loaf in that one episode of “Martin” when you first started reading this). And the increasingly growing criticism as we all become more woke: Why are we still eating slave food if we’re not slaves?

Humans have been eating pig intestines (and other animal intestines) long before American slavery, but among black folks, chitterlings are closely tied with with our history in this country. Slaves were only given the foods no one wanted to eat: The leftovers, the scraps and the organs of animals deemed unappetizing.

It’s a divide that crops up around holidays as we decide which traditions we hang onto, and which ones we need to let go of. But in Detroit, at least, there’s a whole lot of folks not letting go. The only thing that interrupts the silence in the back cleaning area is the doorbell. And it rings often, as people pop in and out for their chitterling orders.

The idea for kickstarting a chitterling-cleaning operation came from Cynthia Tucker, who was watching an episode of Oprah Winfrey’s then-new talk show back in the 1980s. “They were talking about women who were going into business for themselves. She said, ‘why not start cleaning chitlins for people? I thought it was ridiculous at first,” Bruce Tucker says.

“But we started it up at the house, and it outgrew the house quickly,” he added.

Tucker sources his pig intestines from Sherwood Food Distributors, building off a longstanding relationship that allows him to pick only the best of the best. “Those 10-pound buckets in the grocery store, you don’t know what you’re getting. What’s in there is what we call scrap.

“People prefer the longer chitlins. We call them the long, pretty chitlins,” he says. And it’s true, as Margaret Germany, one of the employees, holds up an intestine lining for demonstration. It is long. I wouldn’t call it pretty. But it is long.

The cleaning process is intricate. For chitterlings, all the blood is washed off, and it also removes the first round of feces and undigested bits of food. Then, the membrane is separated from the lining. The membrane is where the majority of “the debris” is, so it is discarded. The remaining lining is washed again and what is eventually served.

“When you go in somebody’s house and you smell the aroma of chitlins and they’re stinking, that means they haven’t been cleaned properly. Whoever cleaned them didn’t know what they were doing,” Tucker says. “When they’re not cleaned properly, what do you think you’re cooking?

Tucker estimates that on a good day with four employees at the Greenfield and Plymouth location, they’re shipping out an average of 35 ten-pound chitterling buckets a day, and get up to 45 or 50 with extra help. They’re sold fresh in bucket or frozen. In recent years, Tucker has expanded his offerings to what he calls “heat and eat”: Fully cooked chitlins sold in individual serving sizes that you can heat and, well, eat — seasonings not included, so you can season to your liking.

Local business booms during the holidays — “Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Years,” store manager Shavon Sanders notes — but savvy marketing online has allowed Tucker to ship frozen chitterlings and hog maws all around the United States and Canada for people craving the dish, but unaware of how to clean them. The result is about $100,000 in annual online sales for one of the cheapest parts of the pig.

The question I had to ask: Do chitterling cleaners eat their own product?

“Oh no, baby, I eat chitlins all year long,” Germany says. “I gotta eat them once in the summertime. I have them Thanksgiving, Christmas, New Years, and then I eat them probably in August. And then I’m right back to work again.

“I’ll put a potato in (my chitlins), seasoning salt, garlic powder, black pepper, every now and then lemon pepper, boil it for about an hour and a half, then pour all that water out — because the grease is in there — then take it and boil it again, and just let it cook until it gets done,” Germany says about how she cooks them. “You’ll know when it’s done because when you pick it up, it’ll fall apart.”

It’s the busy season for Germany, who has been in the business for 13 years, and Sanders, who has been here for 10. “I get happy faces all the time. I’m a people person, I just like to get along with people,” Sanders says in between handling orders.

What keeps Germany coming to work every day is not just the calmness, but the camaraderie. “I enjoy it because we’re like one big happy family around here. I treat them like my kids. I love it,” she says.